Bio Page:

Galileo Galilei was born in Pisa on February 15, 1564, to Guilia Ammannati and Vincenzo Galilei. After moving to Florence at the age of ten, Galileo began his formal education under the tutelage of a Jacopo Borghini, and soon thereafter moved to the Camaldolese Monastery to continue his studies. Galileo flourished there and soon decided that he would live a life of piety as a monk, but his father insisted that he continue education in the sciences and ultimately become a physician. To avoid losing his son to the monastery, Vincenzo Galilei brought him back to Florence and enrolled him in a more traditional institution. Vincenzo eventually sent him back to Pisa to attend the University of Pisa, where he was to study medicine.

Medicine did not appeal to Galileo. Throughout his studies, beginning even as early as his time in Camaldolese Monastery, Galileo neglected his study of medicine for his burning interest in mathematics. At nineteen, he began attending lectures on the works of Euclid and Archimedes, and these studies occupied his thoughts and his time. Though Galileo was still enrolled as a student of medicine, he left the University of Pisa at age twenty-one without a degree.

Four years later, Galileo returned to the University of Pisa to fill the position of Chair of Mathematics. Starting with the abrupt end of his formal schooling, Galileo had written and published and lectured on science, literature, and mathematics. After gaining a reputation as a brilliant mathematician and scientist, he moved to the more prestigious and better-paying University of Padua, where he began to lecture on astronomy. He remained there for eighteen years, during which time he lectured extensively in fields including mathematics, natural philosophy, and astronomy.

Although Aristotelian paradigms of ethereal inalterability were current, Galileo taught his students that the heavens were dynamic. Though Ptolemaic models were considered gospel, Galileo suspected that the Copernican system was more accurate, a belief which he would disclose neither fully nor publicly for many years thereafter. During his time at the University of Padua, Galileo tinkered with the now-famous notions of specific gravity, parabolic trajectory, and pendulum motion, just to name a few. But his most famous and influential work began in 1609 when, at the age of forty-five, Galileo heard whispers of the invention of the telescope.

Rather than seeking out an existing telescope, Galileo re-invented the device for himself and in so doing achieved great magnifying power. By 1611, he had discovered lunar mountains, four of the Jovan moons, the stellar structure of the Milky Way, sunspots, and the rings of Saturn. He also discovered that the planet Venus, like our moon, undergoes phase cycles. This last discovery, Galileo knew, could only be explained by the Copernican paradigm. Galileo began amassing a huge body of evidence for the Copernican system. For fear of violent reactions to his ideas, Galileo kept his discoveries and beliefs secret to all but a small collection of colleagues and family members.

Under Pope Paul V and Cardinal Robert Bellarmine, an Inquisition was conducted in 1616 which condemned the Copernican system and established the Aristotelian and Ptolemaic model as the correct and scriptural cosmological paradigm. Although Galileo did not abandon his Copernican beliefs, he was shielded temporarily from problems with the Inquisition when a friend of his was elected Pope (Urban VIII). The new Pontiff told Galileo that he could write and publish about the Copernican system, provided that he not consider it reality, but merely a mathematical model.

In 1632 Galileo published his Dialogues Concerning Two Chief World Systems in Florence, after failing to receive permission from the church to publish in Rome. His work was banned by the Inquisition as clearly heretical support of an apostate system of thought. Galileo appeared before the Inquisition in 1633 for having authored the work, and he was condemned to spend the rest of his life imprisoned. Luckily, though, “imprisonment” merely meant that Galileo had to be under the watchful eye of a member of the Inquisition at all times—he otherwise could continue his life normally.

Galileo accomplished many other things while under this imprisonment—he designed the first pendulum clock (Christian Huygens built the first working pendulum clock and is usually credited with its invention), wrote Dialogues Concerning Two New Sciences, and discovered how an object moves under a uniform acceleration.

Galileo Galilei died on January 8, 1642.

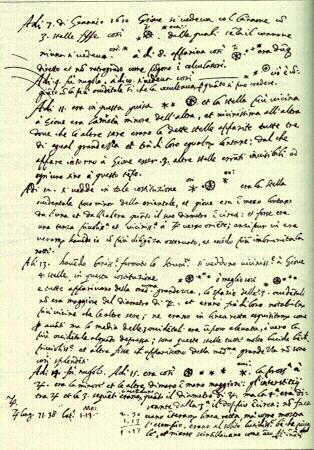

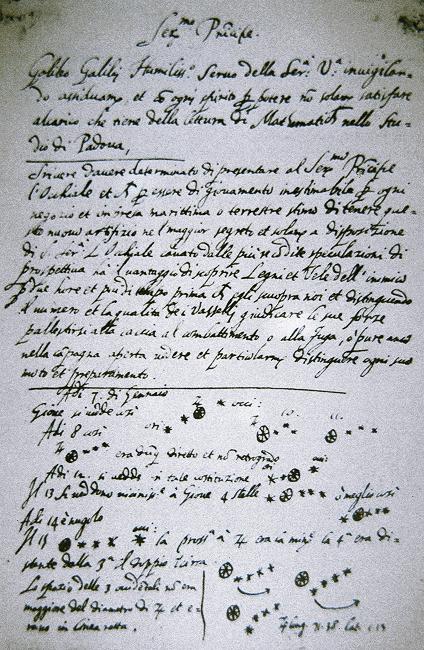

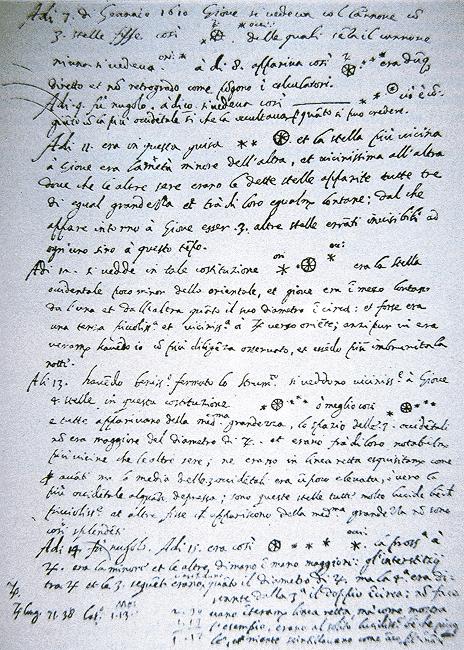

Here are some personal notes written by Galileo: