On the Motion of the Heart and Blood in Animals

~William Harvey~

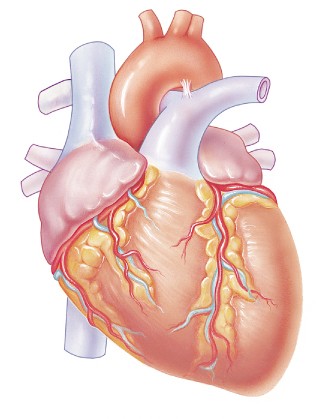

“The heart, consequently, is the beginning of life; the

sun of the microcosm, even as the sun in his turn might well be designated

the heart of the world; for it is the heart by whose virtue and pulse

the blood is moved, perfected, and made nutrient, and is preserved from

corruption and coagulation; it is the household divinity which, discharging

its function, nourishes, cherishes, quickens the whole body, and is

indeed the foundation of life, the source of all action.”

William Harvey, one of history’s most ground-breaking

physiologists, was born in 1578 in Folkestone, England, where, “as

a child he is said to have played with the hearts of animals obtained

at the local slaughterhouse,” (A History of the Life Sciences, Lois

Magner, Marcel Dekker, 1979).

As an adult, Harvey earned a Bachelor of Arts from Caius College in Cambridge

and then went on to study medicine at the University of Padua. He later

returned to London, became a successful physician, was elected Fellow

of the College of Physicians, became a professor of anatomy, and was the

physician of the Biblical James I and Charles I, Kings of England.

The work for which Harvey is most widely renowned is his On the Motion

of the Heart and Blood in Animals. Published in 1628, this work contradicted

the teachings of Galen, the physiological canon of the day. As a consequence

of his controversial findings, Harvey’s medical practiced suffered

as patients were leery of being treated by a doctor whom they deemed a

quack. A clear example of the authoritative dogma that Harvey was up against

is illustrated in the words of John Riolan, Anatomist of the University

of Paris, when he said, “. . . one should not admit Galen to be

wrong. Even if dissection revealed differences, one must presume that

Galen had been right and that nature had changed since he wrote.”

Nevertheless, even with all the criticism directed at him, Harvey remained

a polite and respectful individual who would first listen patiently to

his opponents, and then refute them with an overwhelming amount of observational

evidence to the contrary.

Home Next